Price Oracle Attacks Will Get You Rekt, P.1

What could go wrong when using trusted price feeds?

NOTE: This article assumes the reader has experience with DeFi products and smart contract development, but little substantial security or auditing experience.

Today we’re going to explore Price Oracle Attacks. In the proceeding exploration, take time to follow the included links for more background information. I’d like to make sure you can follow along with me.

Price Oracle Attacks Will Get You Rekt

DeFi has seen, in real money, over $8,000,000,000, lost in hacks. You’ve probably been a victim. If you’ve released anything within the DeFi ecosystem, you might have had it happen to you. During this series, we’ll explain the one technique used to perform these hacks. In this part, we’ll be looking specifically at a noteworthy hack on Inverse Finance.

A Common Tool and a Common Attack

Inverse Finance’s Frontier protocol was hacked on April 2nd, 2022 for $15.6m using a Price Oracle attack.

Price oracle attacks are among the top 10 types of hacks according to Immunifi. To underscore how high the cost is, consider that the two costliest price oracle attacks account for $245,000,000 lost in DeFi alone. Why this keeps happening is that getting useful price feeds in DeFi is not a solved problem, and so developers face trade-offs in providing useful price feeds when building protocols. Popular CeFi exchange Coinbase judges the problem clearly:

There are two main approaches to making asset prices available for DeFi: publishing signed price data from an off-chain source like an exchange, or using prices from algorithmic decentralized exchanges (DEXes) such as Uniswap or Kyber.

Unfortunately, both suffer from major problems. Using data from an off-chain source requires trusting the publisher to post correct prices and keep the signing key safe — the latter historically has proven to be a difficult problem, especially when stakes are high. Similarly, relying on DEX-generated on-chain feeds exposes protocols to various novel attack vectors yet to be fully explored.

Oracles rely on data that might require off-chain trust. Or reliance on potentially faulty on-chain calculations from 3rd-parties. Simply put, a bad price oracle means a bad financial calculation - anathema to the whole concept of accounting.

What makes a Price Oracle attack

It’s leveraging the tradeoffs an oracle chooses. For example, an oracle might need to get the most up-to-date price, but because their prices are determined strictly by reserve ratios, the price is liable to be manipulated by a motivated attacker when the pool liquidity is sufficiently low. As an opposing example, if an oracle is configured to smooth out volatility in prices by taking averages across a long time span, then prices might not reflect true market value. To find a middle ground, some oracles take an average of multiple values. As this first Price Oracle attack is explained, it’ll become clear that vulnerabilities can still emerge.

Price Oracle Attacks by Example

Price Oracle attacks had been done before in DeFi. It wouldn’t even be the last time our protocol in question would be hacked. But, in spite of millions on the line, it happened, all because Inverse Finance missed a vulnerability in how their assets were priced.

To explain, we’ll describe the vulnerability, then explore how it all came together.

Inverse Finance - a Calculated Attack with a Small Pool

Here’s the bottom line for the Inverse hack. As reported by Coindesk:

According to blockchain security firm PeckShield, the Inverse attacker took advantage of a vulnerability in a Keep3r price oracle Inverse uses to track token prices. The attacker tricked the oracle into thinking that the price of Inverse’s INV token was extraordinarily high, and then took out multimillion-dollar loans on Anchor using the inflated INV as collateral.

Specifically:

- The price of the INV token came from the INV/WETH pool on SushiSwap, which forked the Uniswap v2 Pool. This pool provided a price oracle that used time-weighted average prices (TWAP) available to 3rd-parties. This oracle’s price was safe from manipulation, as long as there was enough liquidity in a pool to make the attack too expensive.

- The INV/ETH pool did not have enough liquidity to defend against a price manipulation attack.

- Inverse Finance’s lending pools used the Keep3r network to retrieve the prices from the SushiSwap. This oracle would only use the most up-to-date prices as long as the difference in time between the SushiSwap pool last record and Keep3r’s last record were not equal.

- The attacker made sure the time difference between both records were equal.

Despite the obstacles put in place by Uniswap’s V2 TWAP design, cloned by SushiSwap, as well as the layer provided by Keep3r’s oracle, INV was price manipulated - the oracles in place could not defend against the attack.

Let’s run through the key factors of the attack scenario before we discuss the implementation details. That way we’ll be able to see why each piece of the vulnerability made the attack possible.

The Price Manipulation - Leverage

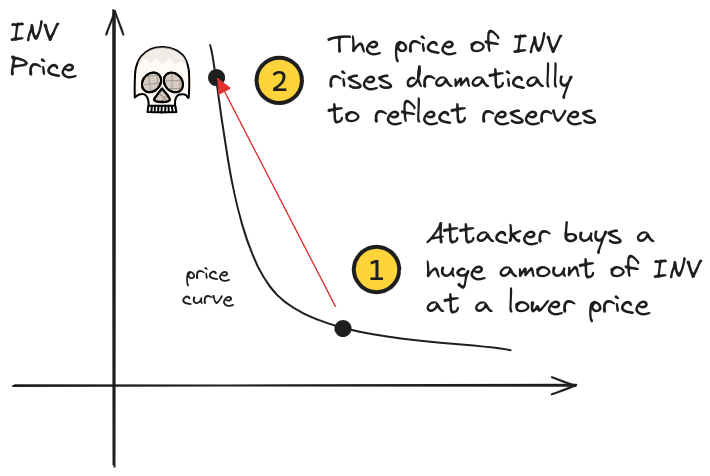

Recall that the Uniswap V2 AMM uses a constant product formula to price its assets. In this case, when a pool has limited liquidity, the constant product formula provides prices with much greater slippage. From the Uniswap docs:

This formula has the desirable property that larger trades (relative to reserves) execute at exponentially worse rates than smaller ones.

For the low-liquidity WETH/INV pool, the INV received after the swap removed so much liquidity that its price in that pool skyrocketed. Any protocols using the price of INV according to that pool would now report this manipulated price nearly 50x higher than originally.

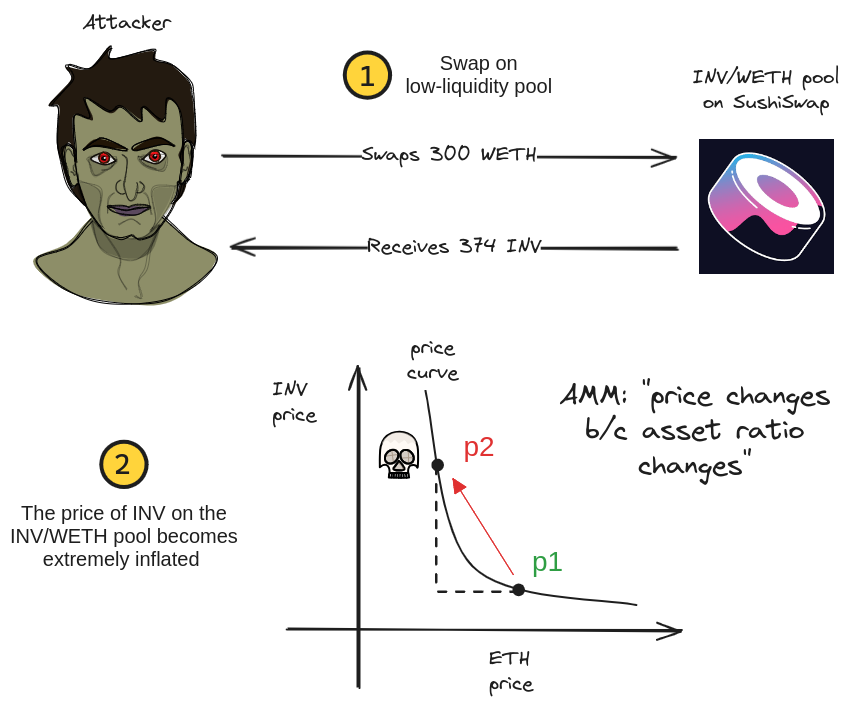

Study the figure below:

In the first step, a low liquidity pool’s was targeted (WETH/INV), and was manipulated by swapping 300 WETH. This caused the price of INV to jump from 0.106 WETH (about $366) to 5.966 WETH (about $20,583), according to analytics firm OKLINK’s report

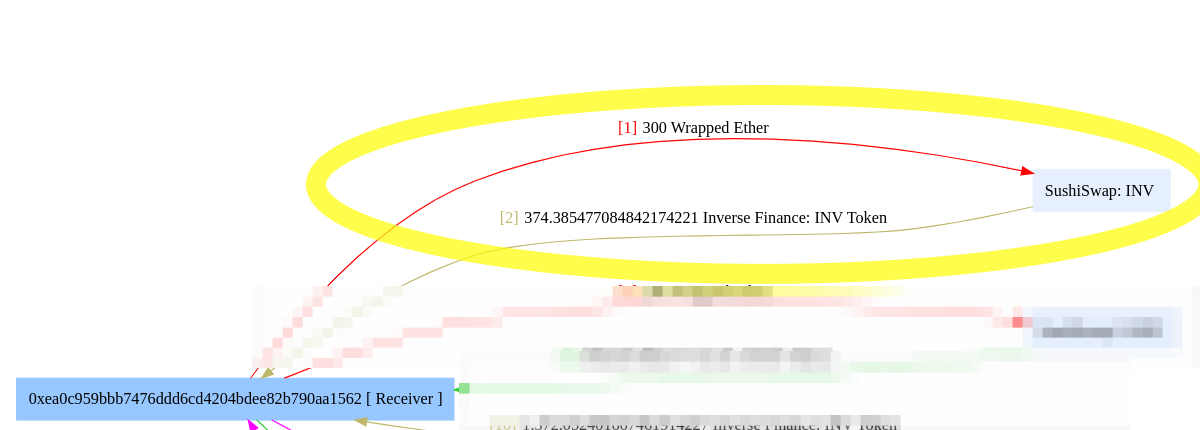

The fund flow highlighted area shown below is the key price manipulation.

Small Pool Big Pressure

The big question is then, “Why is INV/WETH the target when there were other pools around?” In fact, our attacker did swap for vastly more INV using the INV/DOLA pool. However, when we inspect the Inverse Finance lending contract on Etherscan we can see it uses the INV/WETH pool TWAP to determine an account’s liquidity:

The attacker knew that loan withdrawals using INV were priced internally by checking the INV/WETH pool prices, and that the INV/WETH pool had dangerously low liquidity.

When it comes to price oracle attacks, Chainlink describes this instance best:

Poor market coverage can lead to oracles misreporting the price of an asset. Relying on only a subset of all trading environments makes them vulnerable to an oracle exploit if that subset is manipulated, even when the majority of trading environments and the market-wide price remain unaffected.

For example, if an asset is traded across five exchanges and 85% of trading volume takes place on two of those exchanges, relying on the other three low-liquidity exchanges for price inputs would give the oracle poor market coverage. If a malicious actor manipulated the price on those three low-liquidity exchanges, then the oracle would report a price that differs from the actual market-wide price, leading to possible exploits.

Inverse Finance’s oracles had wildly poor market coverage. We’ll see that ultimately only a single market was considered.

Exploiting the Weak Oracle

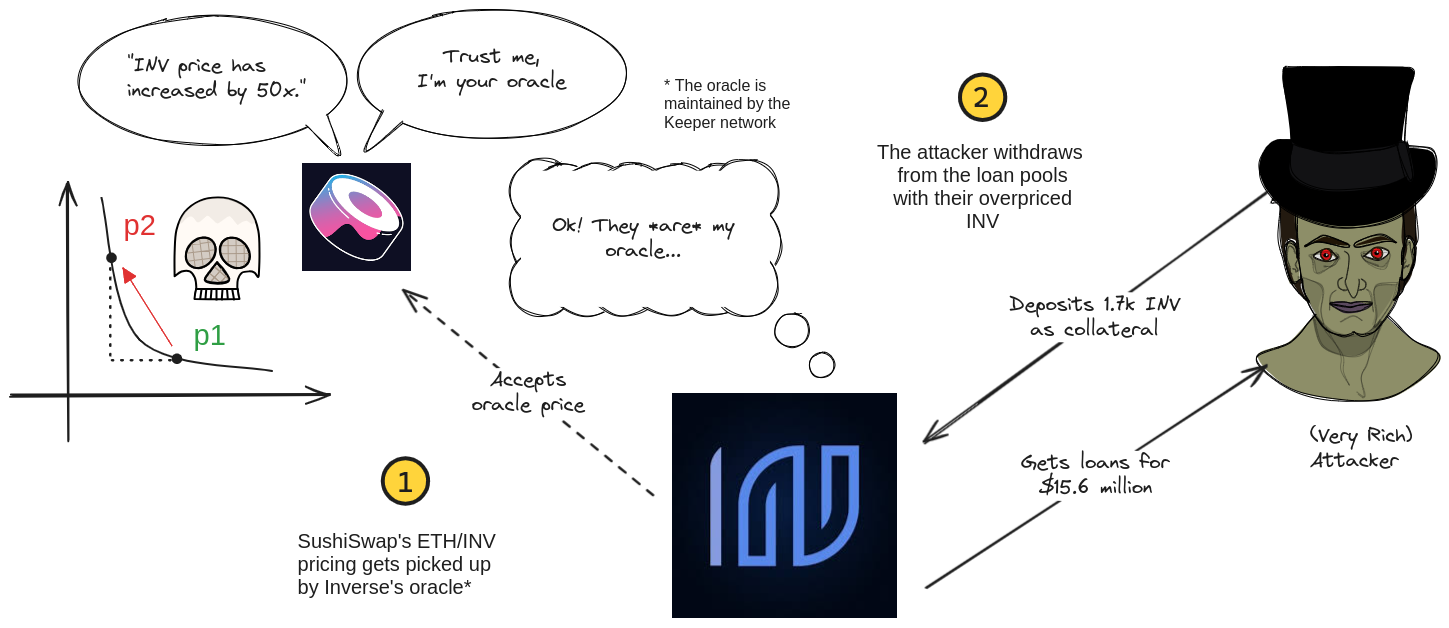

For the first block of the attack, the price of INV has been manipulated near 50x higher. What happens in the next block is shown in the diagram below:

Since Sushi’s pools use the Uniswap V2 TWAP, the attacker must wait until the next block to ensure the manipulated price becomes the pool’s actual price. After manually forcing the pool to do so with sync, the attacker takes his profits by depositing their INV and withdrawing all the funds from Inverse’s lending pools, netting themselves roughly $15.6 million in stolen funds.

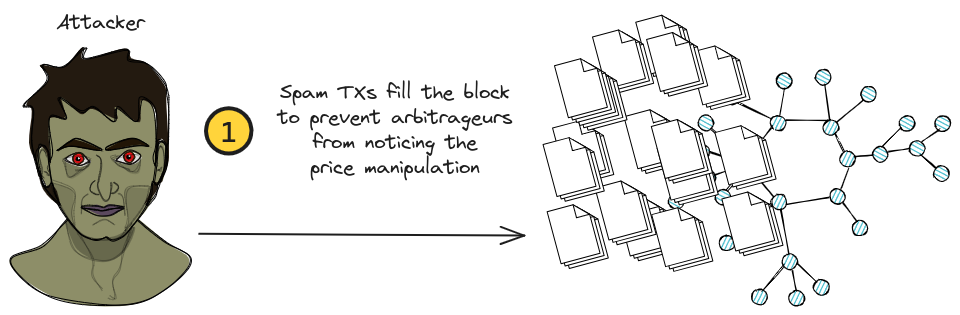

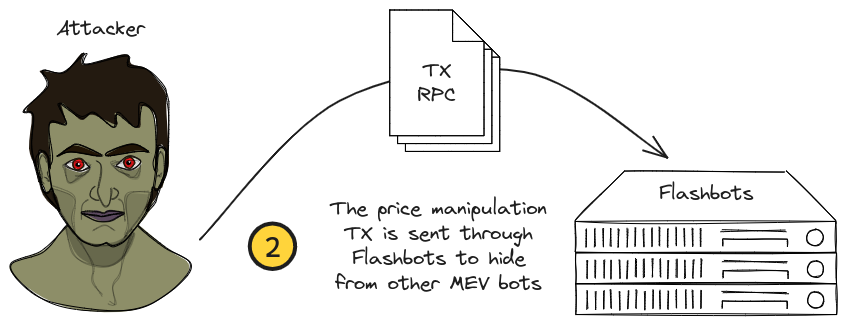

The missing link - MEV

If you’ve been reading and wondering, “How did this guy get away with the attack without be arbitraged to oblivion?” I won’t be exploring the details here but the high level summary is this:

The attacker knows that MEV bots and arbitrageurs are waiting for price discrepancies. To protect against their manipulation getting arbitraged they opted to hide their transaction by directly sending it as a bundle using Flashbots.

Lessons Learned

Let’s walk in the shoes of the devs and roleplay them in a room, the second after the incident.

“Why could the attacker do this?” “What assumptions did they break wide open?” “How can we protect ourselves next time?”

Poor choices and missed chances

Let’s look at the actual oracles in play for this Price Oracle attack. To be clear, the oracles themselves are battle-tested across a wide range of use-cases. It was how they were utilized and the conditions around them that created the vulnerability.

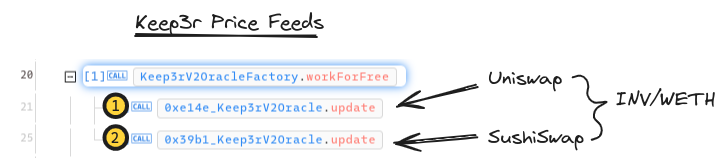

There has been some hand-waving used to simplify the explanation: the Keep3r oracle was designed to use multiple price feeds, and not just the one SushiSwap pool we described in the attack. In fact, the oracle was configure to query both Uniswap and SushiSwap INV/WETH pools for prices.

How is that true, yet still our attacker still exploits the protocol?

SushiSwap - the low-liquidity pool danger

It all begins with the price manipulation on the low-liquidity INV/WETH pool. By leaning on this pool for such a critical function as computing prices of lending pool, the protocol opened the door for a motivated attacker to control how much they could withdraw from Inverse, in bad faith. A single big trade, and the price moves dramatically.

Keep3r Oracle Design - Unused Oracles

In our scenario, Inverse used a Keep3r V2 Oracle as the final say in their price feed strategy. In front of that were feeds from a couple of INV/WETH pools as we’ll see.

Looking into the transaction at the time of the attack, we can see there are two feeds, and each feed’s pair ends up being:

We’d imagine this to to be helpful in the protocol’s defense, if they both contributed to protecting the INV price. That that is not the case. We’ll take note of this while thinking through a key mechanism in the oracle: how Keep3r’s TWAP prices are updated.

Keep3r TWAP - Tradeoffs

NOTE: Keep3r V2 oracles use the same interface as Keep3r V1 oracles

There are two major considerations when it comes to price feeds: Freshness and Security. For the Keep3r V2 oracle, there are two functions that correspond to either consideration:

- Freshness:

current()

// returns the amount out corresponding to the amount in for a given token using the moving average over the time

function current(address tokenIn, uint amountIn, address tokenOut) external view returns (uint amountOut)

This generates a simple TWAP using the difference between the actual pool’s TWAP and the last price records by the pool and Keep3r oracle. Essentially:

\[\text{amountOut} = \text{amountIn} \times \frac{\text{pool.price0CumulativeLast} - \text{lastObservation.price0Cumulative}}{\text{pool.lastCumulativePriceTimestamp} - \text{observation.lastObservationTimestamp}}\]- Security:

quote()

// returns the amount out corresponding to the amount in for a given token using the moving average over the time taking granularity samples

function quote(address tokenIn, uint amountIn, address tokenOut, uint granularity) external view returns (uint amountOut)

This second function creates its own TWAP by averaging the accumulated price observations itself. It supports an arbitrary “lookback” window (granularity), enabling callers to adjust their TWAP according to the desired level of volatility.

Outlining the concept is the averaging logic:

for (; i < _length; i++) {

nextIndex = i+1;

currentObservation = observations[i];

nextObservation = observations[nextIndex];

priceAverageCumulative += _computeAmountOut(

currentObservation.price0Cumulative,

nextObservation.price0Cumulative,

nextObservation.timestamp - currentObservation.timestamp, amountIn);

}

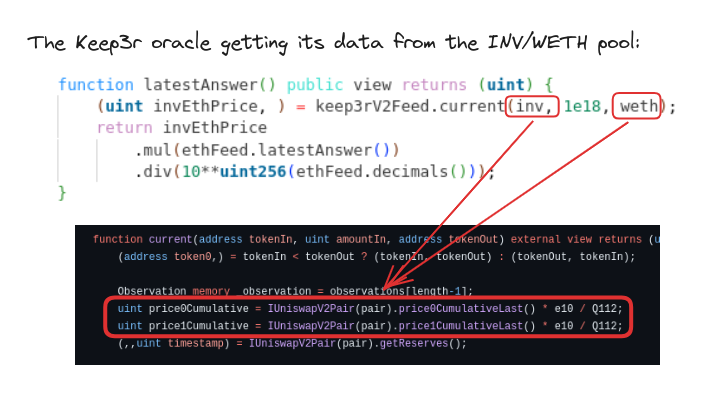

This looks like the function one would like to use in the case of a price manipulation attack. This is not the case for Inverse Finance’s lending platform, and current() is used instead.

Security is traded for Freshness. What ends up aiding the attacker is that Freshness allows the extreme spike in the manipulated price to affect Inverse’s lending rates.

Keep3r’s Freshness function - a volatility sieve

current() samples a single observation and computes the latest data from the pool TWAP. For the purpose of freshness this is essential.

uint price0Cumulative = IUniswapV2Pair(pair).price0CumulativeLast() * e10 / Q112;

// later, compute the price...

amountOut = _computeAmountOut(_observation.price0Cumulative, price0Cumulative, timeElapsed, amountIn);

However, in the case that a pool’s price is manipulated artificially, that manipulated price will pass through to the oracle’s caller with little change compared to a more robust sampling of market prices.

Worse, any defense current() provided against volatility through Keep3r observations is nullified by a vulnerability to stale observations.

Keep3r Vulnerability - computing with canceled terms

The actual computation to generate the price data is this:

amountOut = amountIn * (end - start) / e10 / elapsed;

With the parameters used in the call to _computeAmountOut in current() we can see that expanded to:

If we expand the values in the equation, then cancel like terms, the resulting equation becomes:

\[\text{amountOut} = \text{amountIn} \times \text{pool.price0CumulativeLast}\]Any defenses provided by Keep3r’s TWAP were disabled completely.

Aftermath

In all, these vulnerabilities were missed chances to use a more robust source of fair market value with a more secure TWAP. $15 million was lost by Inverse and the lending pools were frozen The Frontier protocol was shut down and replaced with a new one. Since, inverse has been making regular payments to compensate affected users.

What to ask for next time

In Part II of this series, we’ll examine more deeply the questions security-minded developers and auditors can ask while encountering price oracles.

What kind of questions can help uncover this kind of flaw?

- Is the time window on the TWAP wide enough to handle the expected volatility?

- Could the oracle be getting data from a single, thinly-traded pool?

- Is there sufficient market coverage to be sure the prices reflect fair market value?

- How many price feeds would be necessary to make a price manipulation attack prohibitively expensive?

- Is the chain we use more or less susceptible to MEV?

- Have we exhausted our list of possible attacks to our oracle systems and audited the code to invalidate them?

- Are there any circuit-breakers in place to prevent attackers from using manipulated prices?

Stay tuned for Part II.

– Alex Perez (reentrant)